mag·i·cal (mj-kl) adj.

1. Of, relating to, or produced by magic.

2. Enchanting; bewitching: a magical night

Describing something as ‘magical’ always seems a little over the top – if not faintly absurd in the context of an actual magic show. Nevertheless, it’s at the core of what most of us try to achieve from an effect – which makes the theft of the word by what seems like every consumer electronics manufacturer on the planet somewhat confusing.

Over the last few years we’ve been swamped by an ever-growing number of ‘magical’ electronic devices. And it’s not just iPads. From 3D TVs that promise a ‘magical viewing experience’ to contactless payment systems and digital Smartwatches, ‘magic’ is set to become the standard by which technological innovation is judged.

Perhaps this isn’t entirely unjustified – the technology we’re being sold is sufficiently advanced for us to not know how it works, and in most cases the mechanism is carefully hidden away. The best of these products combine understated elegance with radical innovation – a checklist for any successful magician.

So although it’s upsetting to see the word hijacked into commercial oblivion, it may be that Arthur C. Clarke was right and that any sufficiently advanced technology really is indistinguishable from magic. As a prop maker, it certainly makes my life a little easier. It’s Larry Niven’s riff on Clarke’s original quote that gets me worried.

‘Any sufficiently advanced magic is indistinguishable from technology’

In most cases this isn’t a concern. If you’re accused of harboring a small supercomputer inside a deck of cards you can always demonstrate to your delightfully paranoid audience that this isn’t the case. But of course, this isn’t to say that they aren’t thinking along the right lines. I can think of at least three rather beautiful electronic decks, not to mention all the various dice, coin, and paper-based tricks that involve microelectronics in one way or another.

These near-perfect reproductions of ordinary objects exploit a gap between what’s commercially available and what’s technologically possible. But in a rapidly developing world where technology is designed to amaze and enchant, how do we avoid audiences jumping to the conclusion that some of the more impossible of our effects involve electronics?

The question is relevant regardless of whether you actually make use of electronic props. It you do, it’s fairly easy to switch the offending object for something entirely innocent that can be gleefully dismantled by a skeptical crowd. But given that this should never happen anyway, the challenge is to ensure that the audience never question the objects you’re working with, regardless of whether you actually have anything to hide.

Here’s where industrial design trends are in our favour. After a decade or so dabbling in skeuomorphism (the pleasing but entirely irrelevant ‘click’ made by a camera phone shutter is a good example, as is the wooden background to Apple’s ‘iBooks’ app) consumer electronics are moving towards a more high-tech look and feel. We’re keen to buy into a bright, happy and technological future, and bright, happy, and unashamedly futuristic products are the inevitable consequence. So as long as commercial technology adheres to predictable design trends there will always be a place for the wolves in sheep’s clothing – the objects that masquerade as something far more innocent than they actually are.

Magic and Technology

So is modern technology a threat to electronic magic? Probably not. I just wish they’d stop calling the iPad magical. Enough already.

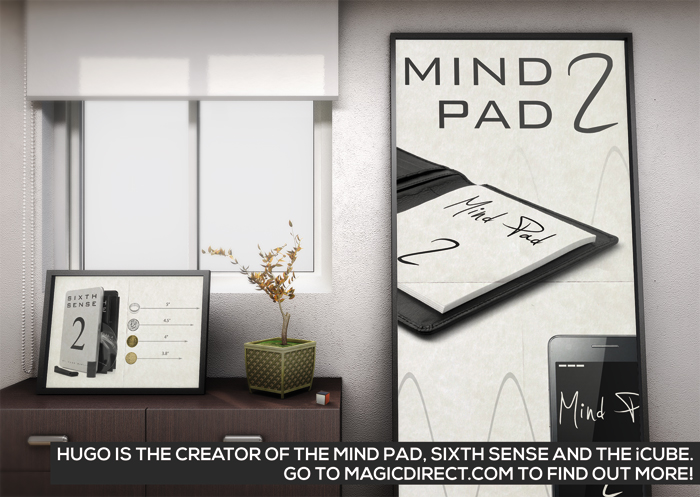

Hugo Shelley is the creator of some of the most groundbreaking electronic magic tricks namely the iCube, Sixth Sense 2.5 and the Mind Pad.